Artificial Intelligence, Regulation, Privacy

In this four-part deep dive into the future of AI regulation, Lucid Privacy Group explores the detail of the new approaches to AI regulation.

Artificial intelligence has emerged as one of the most transformative technologies of the modern era, with the potential to revolutionize industries and reshape societies in profound ways. Business, media, academia, regulators, legislators, and consumers are beginning to coalesce around the idea that the early 2020’s have marked the start of a new technological paradigm.

This new paradigm will be at the very least as transformative as the development of social media and mobile-device ubiquity, but perhaps more akin to the profound social-cultural-economic-technological shifts that came with the dawn of the modern information age in the late 20th Century. Businesses, nation states and scientific institutions are increasingly engaged in an AI technological arms race, in which we are seeing transformative advancement in the technological capability of AI systems.

Whilst we are still most likely a way from ‘true’ machine intelligence (Artificial General Intelligence, AGI - systems that are as intelligent or more intelligent than humans), the next two decades and beyond are likely in part to be shaped by advances in this domain.

Social-cultural-economic-technological revolutions inevitably lead to regulatory change. Just as the information-age revolution eventually led to the proliferation of data regulation, so too will AI technology lead to the development of AI regulation. The revolution will be regulated.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is the simulation of human intelligence processes by machines, especially computer systems. AI can perform tasks that typically require human intelligence such as learning, reasoning, perception, and problem-solving.

Generated by ChatGPT: a Large Language Model using Deep Learning, NLP and other AI algorithms.

Since 2016, AI regulation has been emerging as an area of considerable focus in the global public policy landscape, with significant input from the OECD, the WEF, UNESCO, the G20 and the GPAI, and perhaps most importantly the development of the first legislative frameworks for AI regulation.

In this four-part deep dive into the future of AI regulation, Lucid Privacy Group explores the detail of the new approaches to AI regulation and examines the intersectionality of AI and privacy regulation, evaluating the role that privacy teams might need to (or want to) play in the future world of AI regulatory compliance:

- Part 1: AI Regulation: The EU AI Act and its global implications

- Part 2: AI Regulation: US, UK and other approaches

- Part 3: Intersectional AI and Privacy regulation

- Part 4: The future of privacy teams in AI compliance.

Part 1

AI Regulation: The EU AI Act and its global implications

As AI technologies become more advanced and more ubiquitous, there is growing concern about the impact of AI on individuals and society, across a broad range of areas: product safety, equality, bias, human rights, security, workers rights, weaponization and, of course, privacy and protection of data, amongst many others. In response to these concerns, the European Union (EU) proposed in 2021 a new regulatory framework for AI, known as the AI Act.

The purpose of the AI Act is to establish a comprehensive set of rules for the development, deployment, and use of AI systems in the EU, with a particular focus on high-risk AI applications.

In 2019, the European Commission made a political commitment to address the human and ethical implications of AI in the European Union, publishing the ‘White Paper on AI - A European approach to excellence and trust’.

Following stakeholder consultation, the EC proposed a legal framework for AI that is firmly rooted in foundational EU values and fundamental rights, with the following specific objectives:

- Ensure that AI systems placed on the Union market and used are safe and respect existing law on fundamental rights and Union values;

- Ensure legal certainty to facilitate investment and innovation in AI;

- Enhance governance and effective enforcement of existing law on fundamental rights and safety requirements applicable to AI systems;

- Facilitate the development of a single market for lawful, safe and trustworthy AI applications and prevent market fragmentation.

Intersectional Regulation

The proposed framework cuts across a number of domains, including those related to existing EU law and is fundamentally linked to the rights and freedoms enshrined in the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights. The text of the proposal explicitly links the regulation of AI systems with:

- The right to human dignity (Article 1)

- Respect for private life and protection of personal data (Articles 7 and 8)

- Non-discrimination (Article 21)

- Equality between women and men (Article 23)

- Rights to freedom of expression (Article 11)

- Freedom of assembly (Article 12)

- The right to an effective remedy and to a fair trial, the rights of defense and the presumption of innocence (Articles 47 and 48)

- Workers’ rights to fair and just working conditions (Article 31)

- A high level of consumer protection (Article 28)

- The rights of the child (Article 24) and the integration of persons with disabilities (Article 26)

- The right to a high level of environmental protection and the improvement of the quality of the environment (Article 37)

The framework is also directly linked to the existing suite of relevant EU law, noting that AI systems are already regulated by discrete law in various areas, including:

- The certification of 'safe' products used for non-AI products under the New Legislative Framework - the EU framework for product safety.

- Recent data/digital governance regulations such as the Digital Services Act (DSA), the Digital Markets Act (DMA), and the Digital Governance Act (DGA).

- The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

- The Unfair Commercial Practices Directive (UCPD) for parts related to manipulation and deception.

- Existing consumer and national laws, such as on tort, are also relevant.

Innovation vs Regulation

The proposed legal framework has at its core the concept of proportionality. The AI Act aims to strike a balance between addressing risks of AI without unduly hindering technological development or increasing the cost of placing AI solutions on the market. Legal intervention is tailored to situations where there is a justified cause for concern, and the framework includes mechanisms for dynamic adaptation as technology evolves and new concerning situations emerge. The commission hopes that this approach ensures a proportionate regulatory system that does not create unnecessary restrictions to trade.

Risk-Based Approach

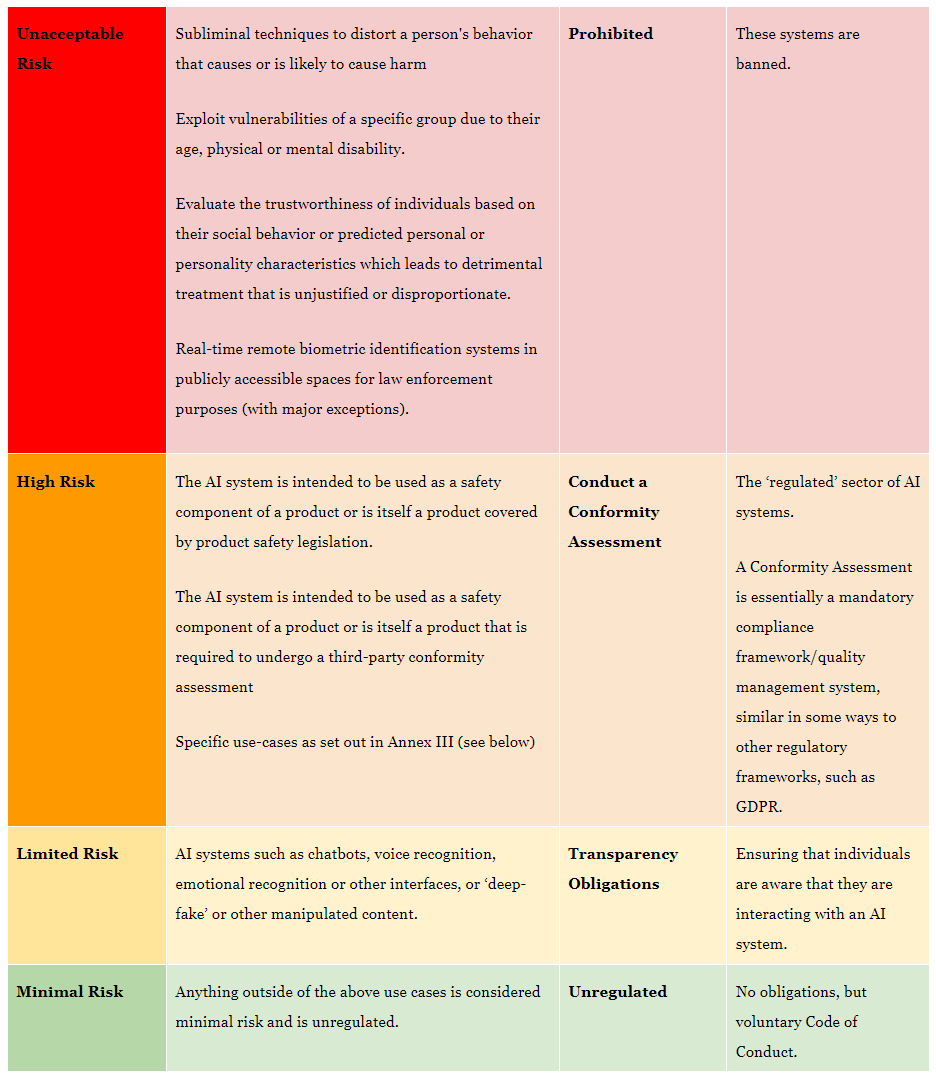

To achieve proportionality, the AI Act is strongly grounded in a risk-based approach, utilizing explicit risk levels to trigger certain obligations and requirements for AI systems under the act. In practice this means that most AI use cases are left largely unregulated or very lightly regulated by the proposed framework, with most of the regulatory burden being placed on providers and users of ‘high-risk’ systems:

The commission believes that the vast majority of AI use cases will exist in the minimal and limited risk categories, meaning that they anticipate that most of the market will remain unregulated.

Outside of the explicit prohibitions, the bulk of the regulation therefore relates to high-risk systems.

High Risk AI

High risk systems are in part prescriptively described in the text of the legislation. These include:

- Critical infrastructures (e.g. transport), that could put the life and health of citizens at risk;

- Educational or vocational training, that may determine the access to education and professional course of someone's life (e.g. scoring of exams);

- Safety components of products (e.g. AI application in robot-assisted surgery);

- Employment, workers management and access to self-employment (e.g. CV-sorting software for recruitment procedures);

- Essential private and public services (e.g. credit scoring denying citizens opportunity to obtain a loan);

- Law enforcement that may interfere with people's fundamental rights (e.g. evaluation of the reliability of evidence);

- Migration, asylum and border control management (e.g. verification of authenticity of travel documents);

- Administration of justice and democratic processes (e.g. applying the law to a concrete set of facts).

The regulated sector of AI systems largely, though not exclusively, align with public-sector/state authority type activities, although this is not explicitly discussed in the text of the act. The thrust of the regulation is towards state/government actors, rather than towards business and the private sector.

Unless a private sector business is involved in one of the above sectors, then the main area of regulatory risk affecting all businesses will be the deployment of AI systems in the workplace/employment context, which is caught up in the regulation. Human Resources departments are therefore likely to be the most impacted function, in general, and will need to be aware of the risks and compliance burdens in utilizing AI systems for employment purposes.

High-risk AI systems will be subject to strict obligations before they can be put on the market, including:

- Adequate risk assessment and mitigation systems;

- High quality datasets that feed the system to minimize risks and discriminatory outcomes;

- Records of activity to ensure traceability of results;

- Detailed documentation providing all information necessary on the system and its purpose for authorities to assess its compliance;

- Clear and adequate information to the user;

- Appropriate human oversight measures to minimize risk;

- High level of robustness, security and accuracy.

- Supervisory Authority reporting obligations.

Like the European Data Protection Board that was established under the GDPR, the AI Act seeks to establish a European Artificial Intelligence Board, whose remit is likely to be similar in scope to the EDPB. We will therefore likely begin to see guidelines, standards and opinions being published by the EAIB once the act comes into force. Such standards will provide useful information as to how businesses should be approaching the development and documentation of the above referenced assets needed to comply with the act.

Users vs Providers

The EU AI Act applies primarily to users (entities using an AI system under its authority) and providers (an entity that develops an AI system or that has an AI system developed with a view to placing it on the market), with the majority of the compliance burden falling on the provider of the system. In fact the user obligations are generally limited to following the instructions of the provider, which is in essence a de facto provider obligation to provide instructions in any case. In this way the regulation diverges from GDPR concepts of controller and processor, and draws more heavily on product-safety law in which developers of systems and products bear responsibility for their compliance.

It is here that the complexity of AI regulation really kicks in. Take as an example ChatGPT or other Large Language Model chat based systems, which are of course at the front line of current AI deployment. On the surface, these systems fall into the limited risk category, meaning that providers can avoid the heavy compliance burden of high-risk category systems. However, such systems can and indeed already are being used for a plethora of use cases by users, that can easily blur into high risk categories in certain contexts.

For example, a user deploys ChatGPT or other LLM chat system into a critical infrastructure project. Such cross contextual uses are part of the power and appeal of AI systems, but such broad deployment approaches may come unstuck in the current European regulatory model. The AI Act appears to force providers of systems to either accept that their system might be used for high risk purposes and therefore fall into the regulated sector, or to prohibit certain use cases via terms and contracts, which raises very tricky contracting and liability issues.

Alternatively, just as Data Processors can become Data Controllers under the GDPR if the facts dictate, perhaps Users will become Providers if they make certain changes to AI systems or use cases outside of Provider instructions?

The Compliance Burden

It awaits to be seen how such issues will play out in reality. It is likely however that developers (and maybe even users) of AI systems will face a substantial and complex regulatory compliance burden once the act comes into force, at least as difficult and costly as those experienced with GDPR and other privacy regulation, probably more-so.

AI developers should be actively examining their exposure to the regulation now, and should have firm plans in place to tackle compliance obligations coming down the pipeline.

Global Implications

The EU AI Act has extra territorial scope similar to the GDPR, meaning that its provisions will apply to non-European companies placing systems on the European market. Again the similarities here with the GDPR give us a crystal ball into how global companies will be impacted by the regulation: the EU is taking the lead with early and robust regulation, with extraterritorial applicability.

On the one hand, this forces internationally scoped businesses to adopt the regulation as a high-bar benchmark for compliance efficiency, since compliance with the EU AI Act will likely guarantee compliance with other regulations - an approach typical to global privacy operations which use the GDPR in the same way.

On the other, we may see global AI providers begin to fragment their product offering across different geographies, with European users receiving a different experience as compared to US users for example. A number of big tech companies have threatened to pull or severely limit products in Europe due to GDPR compliance difficulties, so there is precedent here that may be repeated with AI systems if the European compliance regime proves too difficult to navigate.

We may not see a global proliferation of EU based AI regulation to the extent experienced with GDPR since there is no analog of the concept of the free flow of data, and no ‘adequacy’ decisions needed for other jurisdictions. The transformative power of AI, and the opportunities for economic development, competitive advantage and market disruption, may also allure many states towards a deregulated model.

A fragmented global regulatory model with companies using a ‘rationalized’ EU based high bar approach is a strong possibility. In either case, the compliance burden of AI regulation will be huge for those companies caught in the regulated section of the legislation.

Although the EU AI Act is likely to be the first major piece of regulation in this domain, it does not exist in a regulatory vacuum - other markets are beginning to offer competing models for how best to regulate AI. In Part 2 of this series, we will explore nascent regulatory approaches in the US, the UK, India, China and beyond.