New ePrivacy Rules will Transform Consent — But How?

The European Commission is once again threatening the online industry with the potential of transformational changes to meet their…

The European Commission is once again threatening the online industry with the potential of transformational changes to meet their perception of consumer privacy rights in the digital economy. And while the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) required substantial changes to business process and updates to the structure and content of existing disclosures, the proposed text of the new ePrivacy Regulation imposes substantial new requirements for consent that have the potential to dramatically impact market structure and consumer experience online.

Let’s dive into those requirements and explore the likely impact in market.

Round 1: The initial ‘Cookie Directive’

Beginning in 2009 with an ammended version of the original ePrivacy Directive, internet businesses operating in Europe have been struggling with the requirements of the ‘Cookie Directive.’ At the time, the Cookie Directive required companies to obtain consent before collecting information about the user. Initially, companies feared that they would be required to refrain from any data collection outside of the most basic services directly connected to a user request (e.g. storing a user’s video player position when they pause a video) unless they introduced barrier pages and pop-up dialogues. If your site or business model involved analytics, advertising, or customer profiling of any kind (100% of commercial internet sites), you were going to be impacted.

Under detailed review and after much consternation and lobbying, it turned out that ‘consent’ was a potentially broad term, and individual countries ended up taking different views on whether consent needed to be ‘explicit’ (requiring direct user action) or ‘implied’ (could be implied from the user taking a related action signaling consent). Regulators in certain massively influential markets like the UK, signaled that they would be happy with implied consent for most common data uses (including much of the current analytics and ad market). And while many other markets declared that only explicit consent would suffice, enforcement of this standard varied widely across the EU, and as a practical matter, implied consent became the in-market reality for much of the EU. To be clear, this is not an assessment of the law from a lawyer’s point of view, but of the pragmatic reality that resulted from a combination of confusion, regulatory prioritization, and a commercial path of least resistance.

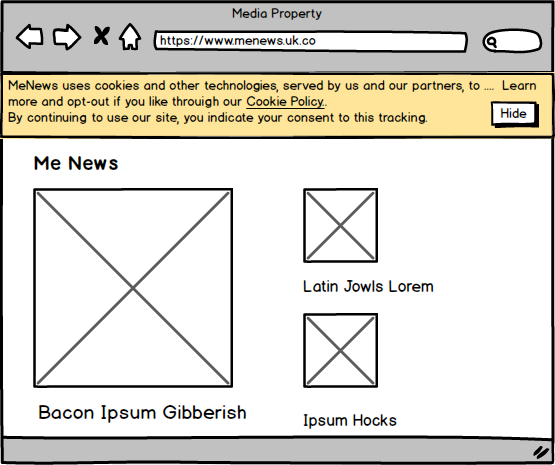

Implied consent gave birth to ‘cookie banners’ — those notice ribbons that you see on websites (especially in the UK, but now in many other markets), which declare that tracking is going to be performed for certain purposes by certain entities, have a link to more information and opt-out options, and state to the user that ‘proceeding to browse the site signals consent.’

Round 2: The ‘Cookie Directive’ comes back as a full Regulation and goes all explicit, all the time

The EU Commission has released a proposed Regulation that will replace the Cookie Directive. Unlike Directives, which in the EU require each country to pass matching legislation, creating opportunities for subtle differences across member states, Regulations take effect on a centralized timeframe managed by the Commission, and the Commission’s final text is binding.

While the current text that we are working with is not final, most observers that I’ve spoken with expect the ultimate version to be substantially similar. The new Regulation includes significant changes to the consent requirement for data collection, including references to GDPR to define terms like ‘consent’ and for enforcement timing (May 2018) and fining authority (2–4% of global revenue).

From the proposed text:

Article 8 Protection of information stored in and related to end-users’ terminal equipment

1. The use of processing and storage capabilities of terminal equipment and the collection of information from end-users’ terminal equipment, including about its software and hardware, other than by the end-user concerned shall be prohibited, except on the following grounds:

(a) it is necessary for the sole purpose of carrying out the transmission of an electronic communication over an electronic communications network; or

(b) the end-user has given his or her consent; or

(c) it is necessary for providing an information society service requested by the end- user; or

(d) if it is necessary for web audience measuring, provided that such measurement is carried out by the provider of the information society service requested by the end- user.

Article 9 Consent 1. The definition of and conditions for consent provided for under Articles 4(11) and 7 of Regulation (EU) 2016/679/EU shall apply.

The non-consent options above (a, c, d) are very narrow exemptions that will not apply to 95%+ of the data collection currently taking place on a modern commercial site. Virtually all data collection, outside of perhaps some first party analytics use cases or services supporting direct user requests, will require consent.

Under the GDPR, consent must be:

- “freely given, specific, informed and unambiguous.”

- “by a statement or by a clear affirmative action.”

Practical implications:

- You cannot require data collection to serve content (or consent would not be ‘freely given’).

- One consent dialogue, referring to generic and wide ranging purposes, is not likely to qualify. Consent should be specific to the entities collecting data, and for their specific purposes.

- Implied consent is no longer sufficient.

Intent of the new Regulation

The principal intention may have been to simply replace a Directive with a full Regulation, in an effort to make compliance requirements more consistent across the EU.

At the same time, the Commission clearly took the time to review how the directive had impacted the market and made an effort to bring it up to speed.

It seems clear from the literature released by the Commission regarding the new Regulation that they are not fans of the cookie banners that have become ubiquitous in certain EU markets. This ubiquity has been disruptive for consumers and has produced a generic ‘click to dismiss’ browsing process that they acknowledge has failed to live up to their original goal of informing and empowering consumers to take control of their data on the internet.

It also seems clear that the Commission is hopeful major platform providers like the web browsers and mobile operating systems will swoop in and provide web level consent and control interfaces that will render site to site notices irrelevant, or least less important. Under this scenario, the consumer’s points of control are centralized and much easier to manage, and their browsing habits become less obstructed, rather than more. But the platform providers have not yet signaled their embrace of these new potential responsibilities. And if they were to see this as their duty, it’s hard to imagine their incentives would align with the rest of the market. Platforms would likely position themselves in a similar manner to anti-spyware vendors, who have an incentive to provide alarmist messaging, trumpeting their ability to ‘protect’ the user from various and un-named ‘nefarious’ actors, and erring continually on the side of blockage.

In this scenario, with pre-run opt-out encouragement from the platforms, the majority of the internet would go dark for the majority of companies. The market would shift to a handful of giants with massive 1st and 3rd party scale (primarily Google and Facebook), and everyone else would need to claw back with pro-active consent dialogues to overcome generic opt-outs with specific consent.

In the long run, this would likely take us full circle back to disruptive consent dialogues across sites, but with a radical shift of market power.

Of course, we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Until the platform providers insert themselves into the role of industry consent gatherers, companies are left to their own devices to secure consent.

Barrier pages will return and consumers will be offered trade-offs

Explicit and detailed consent will almost certainly involve barrier pages, much to the chagrin of the Commission. Individual companies, without the support of platform companies, simply lack a reasonable alternative route to the kind of proactive, pre-emptive messaging system with the consumer that the regulation will require.

Companies will need to be very careful to present the choices offered on the barrier in a manner that does not coerce the user into providing consent to honor the ‘freely given’ requirement.

At the same time, when most sites are financed primarily through advertising, and most publishers rely on networked data pooling to support ad rates (especially everyone below the top 100 most trafficked properties on the web), and the Commission has said that publishers do not need to provide access to content when users block ads, we can assume that reasonable trade offs can be offered to the consumer, and some form of access to content for ads (and related data collection) can be offered.

If the line between coercion and fair trade in this context sounds fuzzy and fraught … it is.

Consent for publishers will need to be granular … but how granular?

The UK’s ICO has released consent guidance for GDPR that suggests each company needs to be individually listed.

You must as a minimum include:

- the name of your organisation and the names of any third parties who will rely on the consent — consent for categories of third-party organisations will not be specific enough;

Most ads are served programmatically at this point, meaning that the publisher does not know in advance who the advertiser will be and multiple parties will have access to the browser to evaluate and ‘bid’ on the ad slot. When you evaluate the 3rd parties that have access to the browser across each ad slot, across each page that the consumer accesses, the final list of ad related 3rd party data collectors on each publisher site will typically reach 30 or more.

In addition to the ad related data collectors, a publisher will often have providers for analytics, CRM, customer service, potentially a DMP, their own retargeting partners, a tag management company, and potentially much more. Not every publisher uses this full set of partners, but this is a common use case for a contemporary media property.

Taken together, this list could easily be 50 or more partners long.

Perhaps the greatest challenge for market participants will be finding a path to compliance that doesn’t upset EU regulators more than ignoring the law altogether. The Commission and major DPA’s, including the UK’s ICO and the Article 29 Working Party, have been clear that:

A) Consent must be specific to each and every company on the site (and each purpose, etc.)

B) Companies must be respectful of the consumer experience, and must not be unnecessarily interruptive.

C) Companies are to avoid barrier pages.

If a site has dozens of partners, how how can these priorities be reconciled? Perhaps the platforms will swoop in and save us, or the way that websites are rendered, optimized, and commercialized will be transformed in Europe.

In the meantime, many companies will be left to their own devices, experimenting with good faith efforts to balance incompatible goals.

Here are a few options:

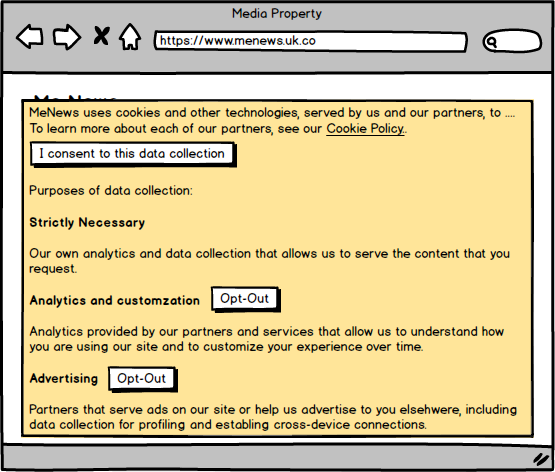

Specific consent organized around purposes:

Organize the partners and ad market participants into categories based on what they will do with consumer data. This has the avantage of simplicity and more likely maps to the the consumer’s interest. The user provides explicit consent for data collection of certain types, for certain purposes, to be performed at this location. Provide a link to invidual companies behind the purposes for the small set of consumers that want to dive into granular detail.

If the consumer does not provide consent, block the loading of these partners and potentially restrict the functionality of the site.

Note that this method does not meet the request of the ICO and Article 29 Working Party to list each company in the immediately visible portion of the consent interface.

If you are using more than four partners, including all ad related technologies, you can address this request, but if you are in the 95%+ set of commercial websites that exceed this threshold, one viewport simply cannot fit every company, along with the data they are collecting and their individual uses of data, your choice is simply: ‘How do I present the company names in a user friendly and informative secondary interface to empower my users to make a real choice.’ Hopefully, an accurate, informative, and readily accessible secondary interface will meet the regulator’s requirements.

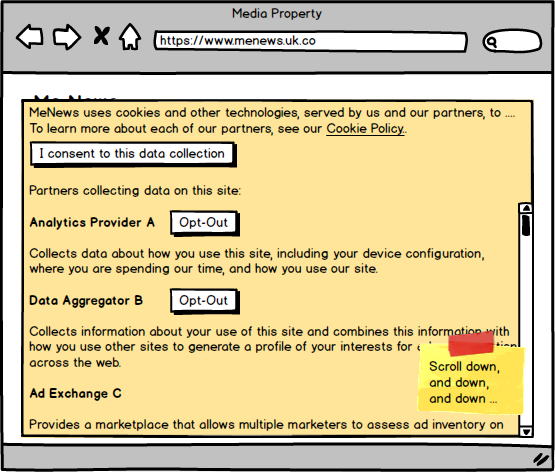

Present company level detail in the primary consent interface:

Present each company collecting data, along with their purpose, to the consumer in a single modal. This maps more precisely to the regulatory requirement. But for most publishers and for virtually every ad supported publisher, the resulting interface would result in a scrollable disclosure that feels more like a terms of service, which no consumer actually reads in full.

Is this actually a superior consumer experience? Does it result in a more informed and empowered digital citizen?

A publisher could make the list smaller if they were to identify the data collectors on each page, and present additional consent barriers on an incremental basis as new trackers emerged, or perhaps do away with barriers and implement a more pleasing customer service bubble or tab presentation. The ICO even recommends this as an acceptable approach (just in time consents). But user friendly bubbles don’t suit an explicit consent requirement where the user absolutely must engage with the interface before proceeding. And leaving aside the technical complexities (its achievable, but not without significant additional investments) the practical impact of this would be to present additional consent interfaces continuously as the user browses from page to page. And the initial consent dialogue would likely still require multiple viewports of scrolling to get through. The consumer experience would undoubtedly be inferior and disclosures would not be noticeably simplified.

And what for 3rd parties?

If you are not a publisher, but one of the technology or marketing partners impacted by this regulation, the above solutions don’t seem to move the ball. First, it’s not clear that a consent dialogue that crams you into a peer group with 50 other companies or hides you behind a click to a cookie policy, would qualify as specific and informed consent to your company, for your purposes. You also have integrations across thousands of invidual websites, and one publisher’s exemplary consent dialogue does little to clear you of consent obligations across your entire footprint.

3rd parties need additional consent mechanisms that:

- Highlight their specific company and data practices.

- Provide a proactive consent mechanism that they can take with them across the internet.

To meet these hurdles, 3rd parties will likely need to strike partnerships with closely held publisher relationships that will provide more specific consent interfaces tailored to short lists of named 3rd parties. This may well become a market adjusting event, with 3rd parties close to publishers benefiting, and consent becoming a necessary currency, coveted by ‘consent cartels’ managed by high volume publishers and their most essential 3rd party enablers.

3rd parties will also need a new technical mechanism to store proactive consent that can be stored and managed across the web. This likely means that the current industry infrastucture, which relies on default tracking outside of the presence of an opt-out, will need to be expanded or overhauled.

There is also some hope that technical standards like DNT, which has been embraced by the Article 29 Working Party, could become a platform to simplify consent across the 3rd party ecosystem. However, important questions remain for this and other technical approaches, including a) whether they can be practically expanded to include all the attributes that regulators will expect for consent collection and management, and b) who gets to control the presentation of these centralized consent dialogues and what, if any, recourse effected companies will have if the interfaces do not fairly describe the market’s data practices.

Next up

There is no clear path that provides for both strict adherence to the letter of the Regulation and a consumer experience that is reasonable and empowering, unless we want to shut down the way that the internet operates for publishers today. We may well find ourselves again in a negoatiated middle ground, where companies, the Commission, and country level DPA’s find a workable solution that each can tolerate that moves the needle substantially towards a more fair and balanced data market, from the the standpoint of the Commission, without burdening the consumer with 50 individual decisions on each site they wish to browse.

We’re about to determine what that middle ground looks like over the next 12 months.

If you found this piece valuable, please leave us a heart and follow us for ongoing updates. We also welcome discussion — please leave your comments and feedback in a response below!

The Lucid Privacy Group actively manages privacy and data protection strategy and operations for startups and marketing technology companies. We come at the issues with a pro-privacy, product and technology orientation, and can translate arcane legalese into real world, commercial terms. Drop us a line at hello@lucidprivacy.io or visit us on the web or Twitter.