The EU Says No Way to Meta's 'Pay or Ok' Under the DMA

The Verge, along with most of the data protection commentariat on LinkedIn reported that

Apple and Meta are the first companies to be fined for violations under the European Union’s Digital Markets Act (DMA). The European Commission announced today that Apple has been served a €500 million (about $570 million) penalty after ruling that its App Store “anti-steering” practices failed to comply with DMA antitrust rules. Meta has been fined €200 million (about $230 million) following similar charges regarding Facebook and Instagram’s ‘pay or consent’ ad model. Both companies have been given 60 days to comply with the ruling, or face the risk of further fines.

The European Commission’s fines came after both companies were unwilling to comply with core terms of the DMA based on earlier decisions the Commission had issued in 2024.

Naturally, Meta and Apple have already vowed to appeal, and Mark Zuckerberg, via Meta's spokesman Joel Kaplan, has already called the Commission’s decision “a tariff” designed to “handicap successful American businesses” while allowing the Chinese and Europeans to do whatever they want. Who wants to place bets on whether the administration will take up that dog-whistle and respond with more 'reciprocal tariffs' against the EU?

Apple’s App Store Rules are a No-No

The decision against Apple, while higher, is far more straightforward, so I'll briefly cover it. In June 2024, the Commission determined that Apple violated the DMA by imposing technical and commercial restrictions on app developers who sought to steer customers towards alternative (and cheaper) app stores and offers outside of Apple’s walled garden. This, the Commission argued, locked app developers into Apple’s high app fees if they sold products in the App Store, or otherwise required developers to pay Apple a “Core Technology Fee” of €0.50 per install assuming they could sell on their own.

In addition to the fine, the Commission ordered Apple to remove these restrictions, and “refrain from perpetuating the non-compliant conduct in the future.” It also closed a separate investigation on user app choices, after Apple agreed to comply with Commission demands. This included making it easier for consumers to uninstall default applications and change default settings on iOS.

Meta's “Consent or Pay” is Not Ok

Similar to other data protection laws (including the ePrivacy Directive and the General Data Protection Regulations), the DMA under Article 5(2) requires user consent when it comes to advertising and the use of personal data. Unlike the ePrivacy Directive and the GDPR, which apply to a broad class of entities, the DMA only focuses on a select group of designated "gatekeepers," including Google, Meta, Apple, Microsoft, and others. Also unlike the GDPR/ePD, the DMA requires gatekeepers to obtain consent any time they combine personal data across their own services and offerings. For example, if Meta uses personal data to target advertisements, users must be given an option to either agree, or be offered a less personalized, but equivalent alternative experience.

In November 2023, Meta introduced a binary ‘Consent or Pay' advertising model. Under this model, EU users of Facebook and Instagram had a “choice” when it came to ads—they could either consent to all of their personal data being harvested and combined for personalized advertising, or they could pay a rather hefty monthly subscription fee (up to €9.99 a month, or €240 a year) for an ad-free version. Other options, like contextual ads, were not available.

The Commission issued a decision against Meta in July 2024, concluding that Meta’s advertising model did not provide users with any real choice to opt for a service that uses less of their personal data, while still remaining equivalent to the original service. “Meta's model also did not allow users to exercise their right to freely consent to the combination of their personal data,” the Commission explained in its press release.

In November 2024, Meta tweaked its advertising strategy by allowing users to consent or receive full-screen, un-skippable ads that relied on less-granular, but still arguably personal, data like age, and location (Noyb has a good write-up here). Both the decision and this fine only cover Meta’s initial pay or consent model. The Commission is currently assessing Meta’s revised approach from November, and has requested that the company to provide evidence of the impact that this new ads model has in practice.

Separately, the Commission agreed to delist Meta's Facebook Marketplace, as a designated online intermediation service. Based on a challenge by Meta and after ongoing monitoring and enforcement, the Commission concluded that Marketplace had less than 10,000 business users in 2024, and was no longer in scope of the DMA’s coverage.

Both Apple and Meta must comply with the Commission’s decision in 60 days, or risk further penalties.

What Makes the DMA Different

The DMA is a fascinating piece of legislation. It's primarily a market competition law, but it's also been effective as a backdoor data protection law. In the two or so years it has been in force, the DMA has motivated gatekeepers to do better in a number of different ways when it comes to user privacy and data, particularly around consent, transparency, interoperability/portability, profiling, and the cross-sharing of data in a compliant way.

Speedier Enforcement: Unlike the GDPR, which has dozens of potentially conflicting data protection authorities across 27 member states, and a time-consuming resolution process, there’s only a single authority under the DMA–the European Commission. In other words, the investigation--> enforcement pipeline is substantially reduced.

The DMA entered into force in May 2023, the Commission designated gatekeepers in September 2023, and opened its first investigations in March 2024 against Apple, Meta, and Google. They then issued a preliminary ruling against Apple in June 2024 and Meta in July 2024, and the fines last week. That’s just shy of two years, which is rocket fast from a bureaucratic perspective.

Compare that to the glacial enforcement pace of the authorities and the European Data Protection Board under the GDPR, which has been around since May 2018. Regulators, especially the Irish Data Protection Commission, tend to move slowly enough, but they're frequently weighed down by conflicting opinions, unhelpful, vague guidance from the EDPB, and so much bureaucratic infighting.

As a Behavioral Billy Club: Since enforcement is faster, I’d argue that at least anecdotally, the DMA is having a greater positive impact on actually forcing behavioral change from big tech. Beyond any flashy fines or headlines, there’s evidence that companies like Apple are making interoperability and distribution better. Cross-sharing and dark pattern consent practices by the likes of Google and Microsoft have been curtailed. And the Commission isn’t just going after low-hanging fruit (like many regulators seem wont to do under the GDPR), so the ROI from a user perspective seems higher.

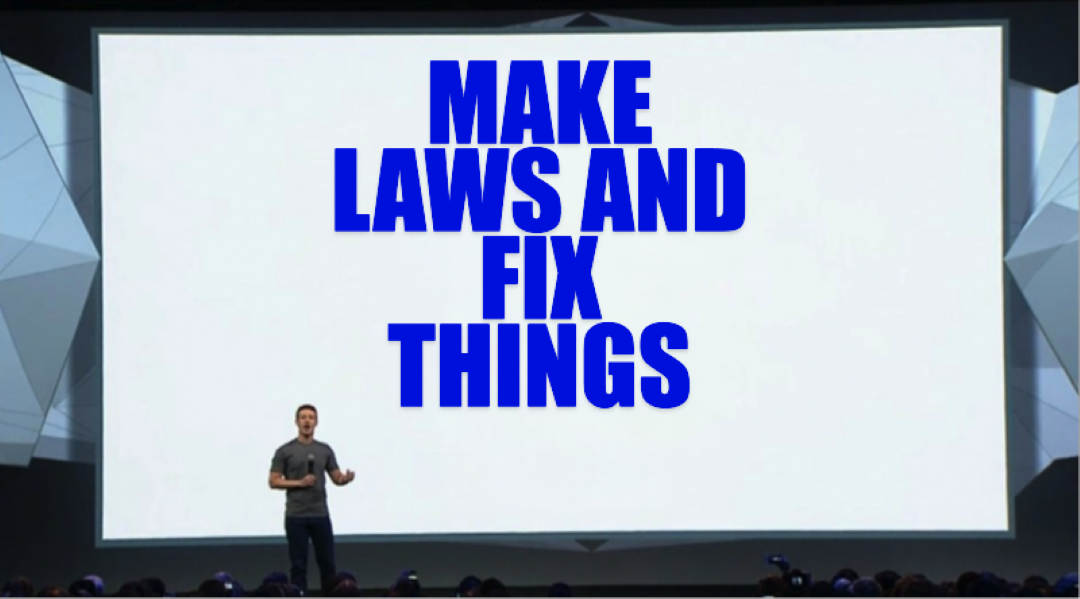

Of course, the DMA isn't technically a data protection law. But within its narrow remit, it's doing a lot so far, and having an unmistakable impact. How this will shake out, and whether the EU will continue to move fast and fix things, remains unknown. But at least there's some progress.