Fired Pixels Under Fire

The 2010s were a time of ‘novel’ patent lawsuits. It seemed like every company was being sued by Tom, Shrek & Harry LLP for sending hyperlinks to mobile users. You know, to service terms and coupons and such.

The cardinal sin? Allegedly infringing an old patent. The lawsuits were frivolous to say the least, and they often targeted small businesses that didn't have the resources to fight back. Some judges stepped in on the side of end users (and businesses) to quash the ‘patent trolls’.

Today, a polar opposite situation is playing out with another embedded technology.

Class action lawsuits du jour have been targeting healthcare providers loading Meta’s tracking pixel on their websites. These cases raise fair and important questions about digital privacy and an existing federal law’s limited reach.

Unsanitary tags

Lawsuits allege major hospitals using Meta tracking pixels shared the confidential medical information of hundreds of thousands of patients in violation of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and state privacy laws. Patients claim Meta used this information to target them ads eerily specific to their health conditions.

To recap:

- HIPAA applies to certain “covered entities” like hospitals and pharmacies who must obtain prior patient consent to share medical information with outside companies.

- Service providers are not given a free pass either -- they must sign specialized “Business Associate Agreements” and be subjected to audits.

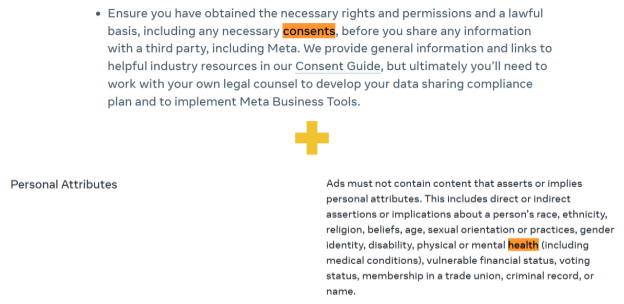

Facebook/Meta is not HIPAA “covered” nor did it sign BAAs with those health organizations. And while its service terms require that organizations permission their data an scrub out sensitive details, the lawsuits allege those privacy policies were not enforced.

Tracking malpractice

While it will be up to judges to decide whether Facebook/Meta is in violation of HIPAA, it's still important for businesses to be aware. And doubly for the overlapping implications under state privacy laws.

Beyond HIPAA, California’s bio-boosted Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) is explicit that collected and inferred information about a person’s health is “sensitive personal information” (SPI). Colorado’s Privacy Act’s definition of “sensitive data” is slightly different, but also includes mental or physical health conditions or their inferences.

That is, data that the recent lawsuits allege can and has been shared with Meta (and who knows who else).

Zooming in:

- HIPAA. The federal law requires “covered entities” like hospitals to provide patients notice and obtain consent to share data with outside entities. Vendors are not exempt, and must sign specialized contracts (BAAs). Non-covered entities like wellness apps and retailers are exempt.

- California (CCPA 2.0). Notice and opt-out from data transfers where data is monetized or otherwise shared with cross-context behavioral ad providers (including for retargeting). And in parallel notice and easy opt-out from out-of-context uses of SPI including through opt-out preference signals like GPC.

- Colorado (CPA + Rules). Notice and opt-in for sensitive data with some wiggle room for in-context and time bound (24 hr) uses. Like in California, opt-outs may be viewed as a withdrawal of previous consents, and effected through signals and default settings.

Leaks in the waiting room

If Facebook/Meta is found to have violated HIPAA because of their policy failures (moderation parallels), it could set a precedent for other companies using similar technology. It would also bestir further attention from regulators who run parallel to HIPAA.

Take Sephora. It settled with California AG Bedoya for $1.2M for a seemingly technical infraction -- ignoring GPC. Yet, the AG specifically noted the kinds of data the cosmetics giant sent out for site analytics and ad retargeting. (Undoubtedly, to a tech provider whose name rhymes with schmoogle.)

Bedoya argued Sephora’s website “sold” inferences about women’s health conditions when otherwise selling in the traditional sense prenatal and menopause support vitamins. “Retailers like Sephora benefit in kind from these arrangements, which allow them to more effectively target potential customers.”

Be as it may, retailers and hospitals are not orderlies in St. Zuck’s Home for Actionable Data. Someone needs to enforce house rules.

And even if Meta is found clear of HIPAA wrongdoings, website operators should still take heed. Sephora’s public dressing-down was a global flex by the OAG.

There is no doubt everyone needs to take careful stock of all their embedded tech. Pixels and unprotected hyperlinks too.

Sensitivity training

Meta’s pixelated legal headaches are far from over. In today’s post-Roe v. Wade situation patients have a right to be ticked. The issue goes beyond tech.

If the decision in Gwyneth Paltrow’s ski accident trial tells us anything (she won, by the way) it's that all sides need to approach the issue of health damage carefully. And with compassion.

It's more important than ever for marketers to work closely with privacy and IT to address these issues head on. Patent trolls will not be the ones to swiss-cheese your brand rep.