Let’s Talk About Authorized Agents

This blog continues the discussion we started in an earlier post, which unpacks The Role of 'AAs' Under Key U.S. State Privacy Laws.

Background

If your company receives consumer privacy requests (aka data subject requests), you’ve probably received requests from third parties who claim they are operating on behalf of a consumer. And lately, the number of authorized agents (“AAs”) seems to be growing. Lucid has seen Optery, Atlas**, Incogni, Freeze, PurePrivacy, DeleteMe, GoInvisible, and to name a few.

Let’s talk about where all these third-party agents come from, their legal obligations and limitations, and the common challenges companies face when working through AA-powered requests.

Given that Optery is the newest agent on the scene, we’ll shed some light on their practices in particular as we go along.

Where did all of these agents come from?

How are there so many AAs and how do they make money if when they do their job, their customers have no reason to stay? Without a doubt, first the GDPR and then the CCPA created a demand for specialized technologies that can help organizations handle DSRs at scale and in coordination with downstream service providers.

Thanks to low pre-Covid borrowing costs, the ‘priv tech’ sector saw sharp growth in 2021. In 2022 the International Association of Privacy Professionals (IAPP) recorded 364 vendors offering a wide range of B2B and B2C solutions. Roughly half of the vendors surveyed offered DSR management capabilities to businesses.

In short, where there’s volume there’s opportunity. Privacy Bee and Mine were perhaps the first to offer complimentary services to both consumers and businesses, raising a number of legitimate concerns within the privacy and business communities as a result.

D2C subscription models

We’ve seen that the majority of AAs operate on a subscription based model, where consumers pay a monthly fee ranging from the price of a latte to an annual Netflix subscription for the AA to send requests to companies on their behalf.

From our experience, AAs find companies to send requests to by (1) mining data broker registries and other public company databases, usually the California data broker registry; and (2) scanning their users’ inboxes to see which businesses they are receiving marketing from.

Some AAs, including Optery, have subscription tiers and the higher the tier, the more companies they send the consumer’s requests to (and of course the more expensive).

According to Consume Reports, which operates a free AA app, Permission Slip:

“The removal services charge between $19.99 and $249 per year for periodic scanning and data removal. Notably, one of the two most effective services in CR’s study, EasyOptOuts, charges the least of the seven services CR tested, at $19.99 per year. (The other most effective service, Optery, charges $249 per year for the “Ultimate Tier” service that we used.).”

AAs prioritize certain data brokers and B2C companies over others, sending consumer requests to a curated list of prioritized brokers and businesses first, then to the next tier of companies and so forth. By observing what receiving companies say in their privacy policies, whether they have particular DSR intake requirements, and how they respond to third-party requests, an AA can build a comprehensive compliance profile on each business of interest.

What are the legal obligations and limitations of AAs?

1) AAs need… authorization from the consumer

Shocker. But in all seriousness, AAs need authorization from the consumer and they need to provide that authorization to the company when they submit requests. What constitutes authorization varies by state and by request.

As we covered in our previous blog, AAs must have authorization from the consumer and provide it to the company when submitting requests, with requirements varying by state. For example, under the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), AAs must present “written permission signed by the consumer,” while states like Colorado, which only allow AAs for opt-outs, accept “commercially reasonable” efforts to verify authority.

Most AAs, including Optery, now default to providing signed written or electronic permission. This authorization, often captured at subscription, allows AAs to easily furnish proof with each request, streamlining the process.

2) Privacy preference signals like GPC are robo-agents

The reasoning behind the California AG endorsing GPC and dinging Sephora for not honoring such opt-out signals is that the signal is, in fact, a technical AAs. If a consumer knowingly changes their browser or device settings, installs and activates a special addon like EFF’s Privacy Badger to broadcast opt-outs to whoever’s listening, it’s the same as using a human proxy.

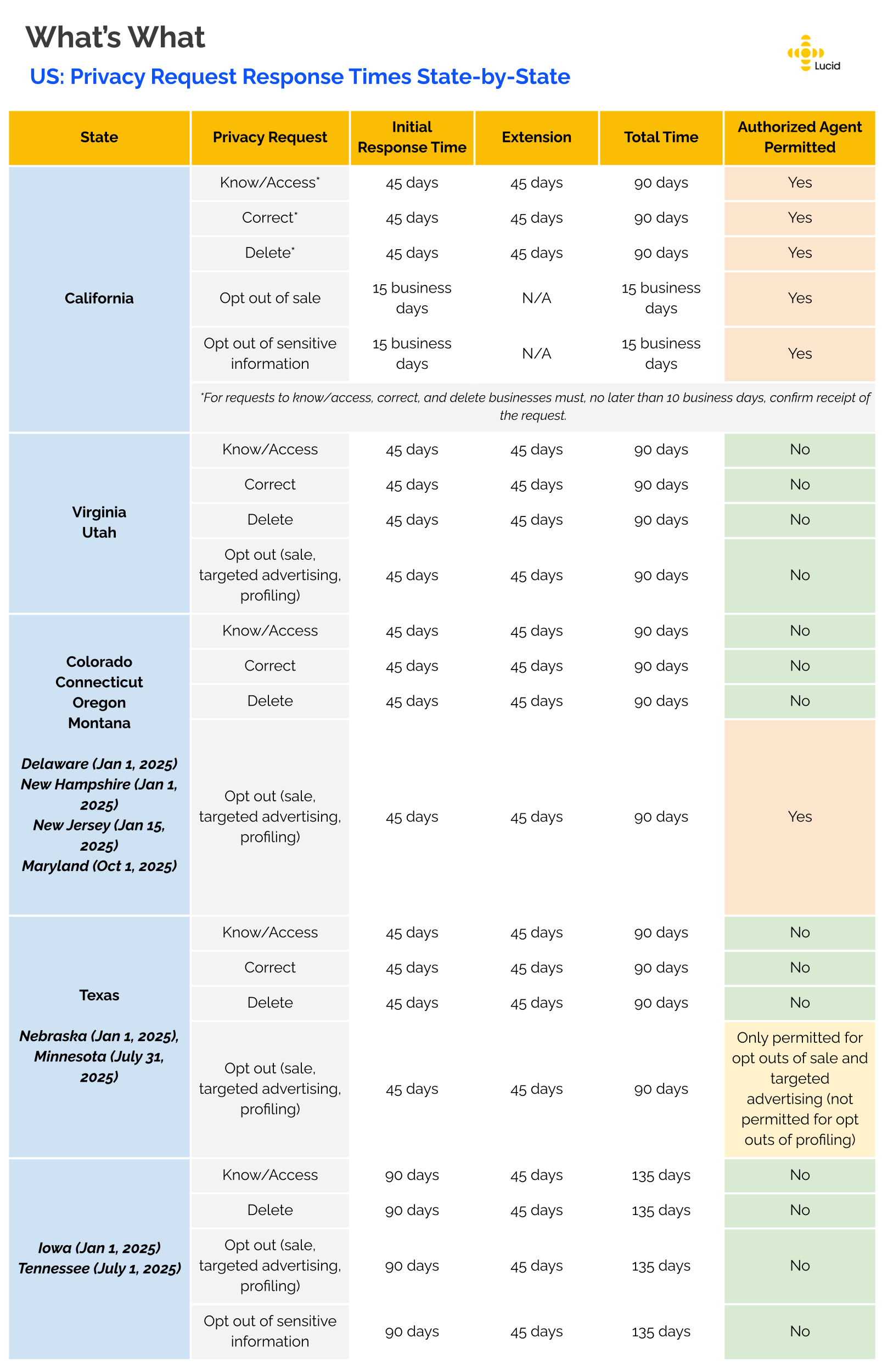

(See the Table below for a comprehensive breakdown of who allows what.)

Navigating common challenges with AAs

1) The AA submits requests they don’t have legal authority to submit.

Many AAs send requests for any consumer, regardless of their state of residence or the type of request. They often cite all potentially applicable laws, even if the law isn't in effect, doesn’t permit AAs, or limits the kinds of privacy requests they can mediate. For example, Optery has sent opt-out and deletion requests for Virginia and Utah residents, even though neither state authorizes AAs, and deletion requests for states like Colorado and Texas, where AAs are only authorized for opt-out requests.

This "whatever sticks" approach can be challenged by companies by contacting the AAs directly.

2) The AA doesn’t provide the consumer’s authorization

This is an easy fix. Respond to the request, asking for the authorization form as required by law. To be fair, this was a common problem a few months back, but as discussed above, it's become standard practice for AAs to preemptively provide signed written authorization as an attachment to a request.

But where it is forgotten, companies have a regulatory obligation to push back, and even buy permitted time to ensure they are dealing with legitimate agents and requests. And where a company has received tons of indiscriminate requests and is struggling to process them all in the legal response timeframe, most states provide for a burden-based extension timeframe.

Optery has learned from its predecessors and provides signed written authorization for all requests it sends, avoiding pushback, at least on this front.

3) The AA sends consumer information, but not the information you need to process the request.

Many AA requests include the consumer's name and home address, but companies often only have email addresses or cookie IDs. And even if the AA provides an email address, in some cases the email provided is a throwaway address provided by the AA. Without the relevant data, companies can't verify if they hold any information about the consumer. And no, you cannot reverse engineer the consumer’s identity using a third-party service.

The solution is to ask the AA for the necessary data points. For opt-out requests, companies can't request extra data to verify identity but can ask for data they already maintain if none is provided. However, responding to each AA request can be overwhelming when there are many.

In such cases, it may be best to contact the AA directly, explain that the company doesn't have the consumer's name and address, and request the email to process the requests. Optery, for example, only sends names and addresses, but they have paused requests to provide emails, which can greatly reduce the volume of requests. On that point…

4) They send hundreds or thousands of requests all at once (one consumer per email)

When faced with a high volume of requests, prioritize responses. Start with the oldest requests with the shortest timelines, and deprioritize AA requests for residents of states without privacy laws. This helps manage large volumes efficiently.

Another option is to reach out to the AA. Ask if they have an API or can send bulk CSV files, and explain your concerns about meeting statutory deadlines due to the volume. AAs are often flexible. Lucid can also help by contacting AAs on your behalf, a method that has proven highly effective.

5) Some of these AAs have relationships with regulators

Unfortunately it's true. Some authorized agents publicize their connections with California privacy figures like Alistair McTaggert and Tom Kemp, suggesting leniency if companies show effort in complying, and implying they won’t report 'good companies' to regulators.

- Atlas goes further by suing noncompliant companies on behalf of consumers, using the threat of enforcement as part of their business model.

- Optery, on the other hand, has shown flexibility. When I reached out for clients needing extra time due to high request volumes, Optery agreed not to report delays beyond 45 days if there was good faith that the requests would be addressed.

Either way, it’s worthwhile to reach out to AAs and let them know you’re trying.

Conclusion

So what should you do if you get a privacy request from an AA you haven’t seen before?

Friendly advice:

- Don’t be hasty, ask around. If you’re not sure how to handle it, do some research, ask around to see how other companies are handling such requests, reach out to Lucid - we’ve probably seen the AA before and if not, we’ve handled many like them).

- Don’t be afraid to reach out to the AA. Ask for them to send requests in bulk files, ask for an API, ask for leniency as you chip away at processing the requests. Either way, from our experience, talking to the AA puts you in their good graces, which is where you want to be when there is a threat of reporting to regulators (or suing if you’re dealing with Atlas).

- Processing requests from states that do not authorize AAs is a best practice. If you choose to process these requests, there is no timeline to respond, so processing these requests is a lower priority. If you are struggling to keep up with the volume of AA requests, take advantage of the lack of response deadlines to tackle regulated requests first.

** Atlas differs from other AAs by operating under New Jersey’s "Daniel's Law" and similar state laws, which protect law enforcement and judges from having personal data like names and home addresses published online. Atlas typically sends bulk requests (sometimes 60,000+ within a few weeks), requiring companies to comply within a short timeframe—10 business days for New Jersey, and even less for other states. Failure to comply within this window can lead to lawsuits, with penalties of at least $1,000 per violation, plus attorney fees and punitive damages. Atlas has taken upon themselves to sue companies for such damages on behalf of individuals, making their rapid compliance demands a significant legal risk.